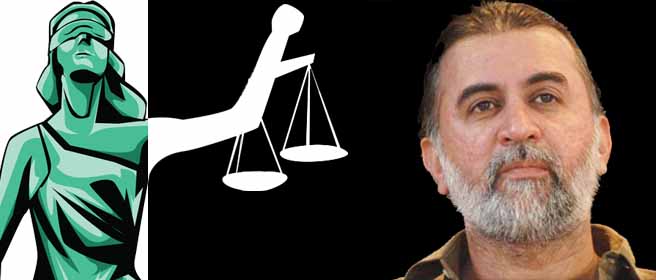

The Rehabilitation of Tarun Tejpal and the Unbearable Lightness of a Sexual Assault

Tejpal’s attempt to return to the literary circuit made a mockery of justice and the countless women who have fought for it.

The vagina should be detachable from the body at no cost or pain to its erstwhile beholder. It makes so much sense, removes the emotional trauma of having it violated, caressed, fingered, penetrated against one’s will. Man has shown no propensity for change and it is high time he foregoes sexual reproduction that requires a female mate, high time he takes his destiny in his own hands and resorts instead to asexual reproduction. Let him carry the burden of producing his offspring. Let him violate his own body, satiate his foul desires by his own. Androgyny is not altogether a new concept.

Who was Bhanwari Devi? Did she, like Atlas, carry the burden of manhood and its seemingly irrepressible beastly comeuppance? Or was it too overbearing for her, the thought and its weight? Crime is identifiable by the possession of loot. But in rape, what is it that the perpetrator possesses after it is over? What is it that he can take home, keep in his wallet? Nothing but his guilt. And that is why rapists think of the vagina in a different way. It is important for them to think so, to see vagina as inert, flaccid, dry of feelings, devoid of emotion. The act of rape at once dissociates man from the society he lives in. He becomes a beast, chooses to forget that he has assaulted much more than a woman’s vagina. He forgets that he has assaulted, laid claim to, the intangible – human emotion.

Complaining about the media is easy and often justified. But hey, it’s the model that’s flawed.

Pay to keep news free and help make media independent

How does one deal with a crime without accounting for the emotional trauma? “Who is Bhanwari Devi?” is a question that cannot be answered by reading law reports or judgements. In there, in those dusty crumpled pages left to rot in the corridors of court houses, she has been reduced to a litigant, someone who tried to bring those who gang-raped her to justice. The long and arduous process of law has reduced her to a case number, nothing more.

When you approach the temple of justice you are supposed to leave emotions behind as though they were a pair of chappals. You go in with folded hands and narrate your horror, and the law, the sacrosanct law that governs a so-called civilised society, shouts: “Bhanwari Devi haazir ho!” And in walks Bhanwari Devi and stands in the dock, a thousand eyes trained on her, a hundred voices countering her cries of anguish.

Justice is the most dehumanising of human inventions if one considers that humans are emotional beings. Of course they are. But justice delivered with passion becomes vigilante justice. When one approaches the court, one does so in large measure for the sake of posterity. A judgement is quoted and imbibed in other judgements that will follow months, years, even decades later. Now think of the superhuman act of Bhanwari Devi or of the millions of other women who asked for justice.

“Who is Bhanwari Devi?” I ask again. Bhanwari Devi is a symbol. She never wanted to become a symbol, but the simple act of demanding justice for herself turned her into one. She initiated unintentionally a chain of events that led to far-reaching changes in the law that defines what rape is. Her ordeal entered the typewriter like a blank sheet of paper and what emerged after decades of typing, notarising, amending, reformulating, restructuring, was a preamble. A preamble that a few like Tejpal probably wish never existed.

Vishaka & Others Vs State Of Rajasthan & Others

Date of Judgment: August 13, 1997

Bench: Chief Justice of India JS Verma, Justices SV Manohar and BN Kirpal

In 1997, Vishaka, a non-government organisation (NGO) fighting for justice it felt was denied to Bhanwari Devi, filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court, demanding that sexual harassment at the workplace be looked at afresh and laws be made to define strictures and punishment. The Supreme Court took serious note of the writ petition, castigating the government and law machinery for not having drawn up guidelines to the effect.

“This Writ Petition” said the court, “has been filed for the enforcement of the fundamental rights of working women under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution of India in view of the prevailing climate in which the violation of these rights is not uncommon.

The immediate cause for the filing of this writ petition is an incident of alleged brutal gang rape of social worker in a village of Rajasthan. That incident is the subject matter of a separate criminal action and no further mention of it, by us, is necessary. The incident reveals the hazards to which a working woman may be exposed and the depravity to which sexual harassment can degenerate; and the urgency for safeguards by an alternative mechanism in the absence of legislative measures.

Taking note of the fact that the present civil and penal laws in India do not adequately provide for specific protection of women from sexual harassment in work places and that enactment of such legislation will take considerable time, it is necessary and expedient for employers in work places as well as other responsible persons or institutions to observe certain guidelines to ensure the prevention of sexual harassment of women.”

The bench went on to formulate 12 guidelines that included duties of the employer, the definition of sexual harassment, initiation of criminal proceedings and the setting up of a complaints committee. “Accordingly,” the bench concluded, “we direct that the above guidelines and norms should be strictly observed in all work places for the preservation and enforcement of the right to gender equality of the working women. These directions would be binding and enforceable in law until suitable legislation is enacted to occupy the field.”

Seventeen years hence, there has been no suitable legislation enacted by our Parliament so as to occupy the field. It follows that the Vishaka guidelines as they have come to be known, are binding and enforceable.

“Who is Tarun Tejpal?” is a question that will be asked in the coming week by many who don’t already know of the man. Tarun Tejpal once ran an outfit called Tehelka that, as it turned out, never followed the Vishaka guidelines. In December of 2013, during a festival called Thinkfest – also run by Tejpal – a woman employee of Tehelka accused Tejpal of sexual molestation and assault. Flustered, Tejpal wrote to his conscience a letter of admission as cringeworthy as the sound of fingernails dragging on a blackboard. When the charges against him were brought by the victim’s lawyers, the world got to know that, in the victim’s eyes, what Tejpal had committed was rape. Tejpal denied the allegation. He was mortified at the thought that what he did could be construed as rape. Indeed, a copy of the November 30, 2103 court verdict on the anticipatory bail hearing in the Tejpal Vs State of Goa case (available at http://northgoacourts.nic.in/; Application No. 573/2013) elaborates on the desire of Tejpal to refute all allegations of rape.

“…The applicant has stated that throughout his career he has striven for transparency and accountability in public life…”

“…The applicant has stated that he and his wife had attended an annual conference by name THINK 2013…”

“…The applicant has stated that…he had a light-hearted bantering with one of the lady colleagues…a further meeting took place between them which lasted for few seconds…”

“…she continued to party and was completely normal and friendly all throughout her stay in Goa. She was at every party and social event through the conference and stayed out late into the night…”

“…The applicant has stated that the Complaint is motivated, false and an afterthought…”

“…Learned Senior Counsel Ms. Geeta Luthra has argued on behalf of the applicant. She has argued that the applicant is a Journalist of global repute and has taken 50 years to build this reputation. Throughout his career, the applicant has been avid campaigner against corruption as well as attempts to tarnish secular fabric of the country and in the process has made many enemies within his fraternity and the political parties…”

“…the delay in reporting the said incident as well as the subsequent conduct of the victim is an indication that it is a doctored document…”

“…the arrest leads to great ignominy and disgrace not only to the accused but also to the entire family and at times to the entire community…”

“…the law under which the applicant is sought to be arrested, is draconian.” (Emphasis added.)

Make no mistake – the word “draconian” is intended to serve a purpose. Had the incident occurred during Thinkfest 2012, it would not have amounted to rape. Come Thinkfest 2013 and things were a little different. Allow me to explain:

After the gruesome Nirbhaya gang-rape incident of December 2012, Justice JS Verma was asked to formulate amendments to criminal law that pertained to rape and sexual harassment. This is the same man who helped draw the much-needed Vishaka guidelines back in 1997 when he was the serving Chief Justice of India.

In less than a month, he along with two other legal luminaries came up with an astonishing 644-page document titled: Amendments to Criminal Law.

Crucially, the definition of rape was amended. While earlier it was specific for penile penetration, Justice Verma asked for a change in Section 375 of the IPC by stating the following: “We have kept in mind that the offence of Rape be maintained but redefined to include all forms of non-consensual penetration of a sexual nature.”

On March 21, 2013, the Parliament passed the Criminal Law Amendment Act that included the new, broader definition of rape (“sexual assault”) as proposed by Justice Verma. Exactly one month later, on April 22, 2013, Justice Verma passed away.

Justice Verma’s legacy – the Vishaka guidelines and the amendments to our Criminal Laws – are not draconian. Those who refuse to accept them as binding are.

Unspeakable crimes are committed against women in this land, most of them by men who the women trusted. The politicians and the police never lose an opportunity to declare that the Western world reports more rape cases than we do, forgetting conveniently that the operative word here is “report”.

Ever since Tejpal’s ignominy came to light in December 2013, hundreds of articles and news shows have condemned him and his organisation to history. At the same time, there is also little doubt that he will return to his full former glory. His rehabilitation, through the upcoming Times Literary festival, was to be the first step in this direction. But as the news leaked out, the organisers got cold feet – not because they felt it was morally wrong to have invited an alleged rapist but, rather, because they “didn’t want the festival hijacked by extraneous noise”.

Strange that the very people who in December of 2013 and through “our” channel, proclaimed to be supporting the voice of the people, the voice of justice, the voice of what is morally right, now consider this voice as mere noise. Make no mistake – this noise shall be cancelled out. The rehabilitation will happen and it will happen soon. Phoenix is probably an Indian myth not Greek.

This is no longer about Tejpal. No. This is about the respect we as Indians are prepared to give to our laws and our institutions and the people who make them work under the most trying of circumstances. Tejpal is back but what of his victim? What of all our shouts of support for her a year ago? Yes, she was and is brave. But it is crucial that, despite the Tejpal rehabilitation plan now well underway, one does not lose sight of the impending tragedy that befalls every such case. In our country brave is not she who speaks up, it is she who has knocked at the gates of our courts and is awaiting justice.

Before Bhanwari Devi there was Mouchette, a little French girl who suffered at the hands of men just like Bhanwari Devi did. Tragedy and sorrow know no boundaries. A woman’s fight for justice is universal, as are its trappings and hardships.

But how brave Bhanwari Devi has been, and how brave Tejpal’s victim is, becomes apparent when one gets to know the ultimate fate of Mouchette:

No one can deny that ours is a waning state, that all the organs of this state are failing one by one, that justice for so many women still remains a distant dream. Then again, even in the face of such travesty, because of men like Justice Verma we finally have a set of laws that aim to give a woman back her body. It is up to us to never let vagina become detached again, from the workings of the body, from the workings of the mind. A draconian state of being would be one where the rehabilitation of Tejpal succeeds while that of the victim fails. If that were to happen, Justice Verma for one would be relieved that he is no longer among a people such as us.

This article first appeared in newslaundry on Nov. 24, 2014.